105. The Supreme Court and the 2024 Election, Part I

A quick overview of the election-related disputes that are likely to reach the justices between now and next Tuesday—and the big one that almost certainly won't.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

Although I wanted to write about a new emergency application in an immigration case in which a Texas district court and the Fifth Circuit are … acting shadily, I’ll save that for this week’s bonus issue on Thursday. Rather, my focus today, eight days out from Election Day, is the first of what I fervently hope aren’t that many posts about the Supreme Court and the 2024 election—a look at the cases that, at least at this juncture, already are at the Court, or are likely to shortly get there (and one important case that almost certainly won’t). A lot can happen in eight days, but at least as of this morning, it does not look like the Court is likely to do anything this week that will produce big impacts next week—something that we might all be able to agree is a good thing.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

As expected, last week was pretty quiet at the Court. The justices handed down a regular Order List on Monday, the biggest headlines from which were the four grants of certiorari—bringing the total number of cases to which the justices will give plenary review during the October 2024 Term to 47. I wrote about three of the four grants, all of which have to do with the proper venue in challenges to actions taken by the Environmental Protection Agency, in last Thursday’s bonus issue. The fourth involves a technical dispute over the factors federal judges can consider when revoking a “supervised release” condition of a federal prisoner’s sentence—the subject of a deeply entrenched “circuit split,” in which the nine federal courts of appeals to consider the question split 5-4 on the answer.

That was it for action by the full Court last week. And no full Court action is on the calendar for this week; we do not expect a regular Order List today (because there was no Conference last week). Instead, the justices are next set to meet in person for a regularly scheduled Conference this Friday (the orders from which will drop next Monday), and they will next take the bench (for the beginning of the November argument session) at 10 ET next Monday morning.

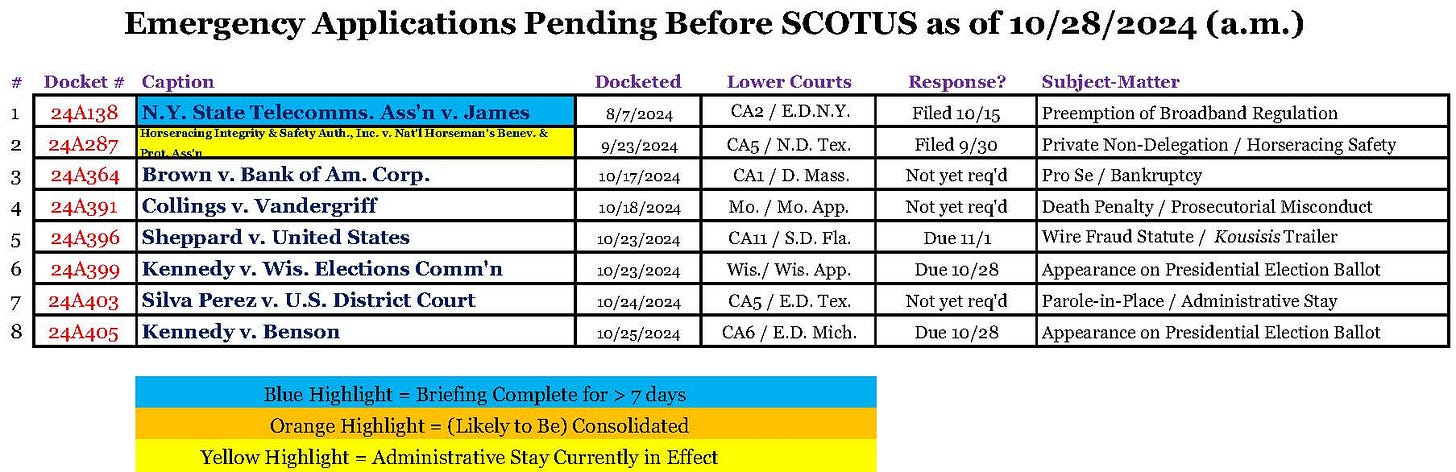

As a result, if the Court is going to make news this week, it’ll almost certainly be with respect to emergency applications. Counting the new immigration application noted above, there are eight applications currently pending—including two from Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. that are directly related to the election:

But it’s a virtual certainty that the denominator will increase before the week day is out. Hence the focus of this week’s “Long Read,” below.

The One First “Long Read”:

Election Cases (So Far) Heading to SCOTUS

The two RFK Jr. cases, about which more shortly, are the only election-related disputes currently pending1 before the justices. In today’s post, I want to flag three other disputes—two of which could reach the Supreme Court this week, and one of which almost certainly won’t (which is news unto itself). It is entirely possible that some other case will spring up between now and next Tuesday that gets to the Court in time to make a difference, but as I’ll explain with regard to the Fifth Circuit’s Mississippi ruling (the one that almost certainly won’t make it), there are reasons why, even if that happens, it’s unlikely that the dispute will directly affect the election.

The RFK Cases

As noted above, the two cases already pending before the Court are a pair of emergency applications from RFK Jr. seeking to take his name off of presidential election ballots in Michigan and Wisconsin. (Kennedy has sued in some states to get back on the ballot, and in others to get off of it, with the pattern seeming to be directly related to which is the best outcome for former President Trump.) The relevant circuit justice (Kavanaugh for Michigan; Barrett for Wisconsin) has called for responses to the applications by this afternoon, but I’d be shocked if these were to go anywhere. Not only is it way too late in both jurisdictions (where early voting is well-underway), but when Kennedy filed a similar application last month trying to get on the ballot in New York, it was summarily denied by the full Court without any public dissent or separate writing. I expect similar outcomes here.

Pennsylvania: Naked Ballots

One of the two cases that’s likely to reach the Court today comes from Pennsylvania, where the Republican National Committee has already said that it will ask the justices to take emergency action to freeze a Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruling that would allow for voters who cast invalid absentee ballots (by not placing their ballot in the required “secrecy sleeve,” hence the term “naked” ballot) to cast provisional ballots in person. (Under the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s ruling, the provisional ballot will be counted if and only if the naked mail-in ballot is not.) If this sounds familiar, it’s quite close to one of the only genuinely contested legal issues in the 2020 presidential election—whether Pennsylvania could count mail-in ballots that were postmarked by Election Day, but didn’t arrive until up to three days later. There, too, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court issued a ruling interpreting Pennsylvania state law in a manner with which the state legislature disagreed, and the question was whether the Pennsylvania Supreme Court was entitled to the last word. (It ended up not mattering in 2020 because President Biden’s margin of victory in Pennsylvania far exceeded the total number of ballots affected by that dispute.)

The substance of this dispute comes down to the so-called “Independent State Legislature Theory”—the idea that the federal Constitution imposes at least some limits on the ability of state supreme courts to interpret state legislative enactments relating to federal elections. The Supreme Court in Moore v. Harper didn’t slam the door on the theory, but it didn’t warmly embrace it, either; the majority opinion left open the possibility that there will be cases in which state supreme courts go too far, but quite explicitly declined to explain what those would be. And there are also some procedural issues with this specific case (which is directly related to the 2024 primary election, not the general election).

For all of those reasons, it’s hard to imagine that the justices will be in a hurry to step in here. And, as in 2020, it may not matter either way; over at the super-useful Election Law Blog, NYU Law Professor Rick Pildes has a post suggesting that, even with a bunch of (potentially inaccurate) one-sided assumptions about their partisan skew, counting such provisional ballots could alter the Pennsylvania margin by somewhere between 400 and 4000 votes. It’s not implausible that Pennsylvania will be that close. But if it is, suffice it to say that this won’t be the only case that matters.

Virginia: Late Culling of the Voter Rolls

A second dispute likely to reach the justices later today involves Virginia’s efforts to cull from its voter rolls individuals who didn’t have, in the state’s view, adequate proof of their U.S. citizenship on file with the state Department of Motor Vehicles. (This is part of the broader universe of false or wildly overexaggerated claims from one side of the political spectrum about non-citizen voting.) The U.S. Department of Justice in one case, and a group of voters and non-governmental organizations in another, sued Virginia, arguing that its efforts violate the National Voter Registration Act of 1993—which imposes a 90-day “quiet period” in the run-up to elections during which states are barred from implementing any systematic program aimed at removing the names of ineligible voters from voter registration lists. The quiet period exists not to protect the ability of ineligible voters to vote, but so that, in case the state errs, eligible voters have enough time to correct the error before Election Day itself.

On Friday, a federal judge in Virginia granted a preliminary injunction—ordering Virginia to restore to the rolls the 1600 registered voters it has already culled under the program on the ground that the program likely violates the NVRA, and to stop removing other voters from the rolls under the same program. Governor Youngkin quickly appealed that ruling to the Fourth Circuit, and also sought a stay. Late yesterday, a unanimous panel of the Fourth Circuit refused to grant a stay (except as to one very small and not especially significant part of the district court’s injunction), filing a six-page opinion explaining its rationale—and why Virginia’s statutory interpretation arguments are remarkably weak. Youngkin has already said that he’ll be seeking further relief from the Supreme Court, perhaps as early as today.

The Virginia case raises a potentially awkward problem for the justices. On one hand, the so-called “Purcell principle” is supposed to augur against federal judicial intervention in the run-up to an election, ostensibly to mitigate the risk of voter confusion. On the other hand, in this case, (1) the underlying legal violation was itself of a rule limiting election-eve behavior by states—a federal statutory rule that would be completely unenforceable if Purcell (which is, at best, a judge-made principle of equitable relief), applied; and (2) the alternative is not “confusion”; it’s disenfranchisement. Moreover, as the Fourth Circuit explained in its brief opinion denying a stay, the action being challenged here is not a state legislative enactment, but rather a state executive order itself issued close to the election.

My own best guess is that the Supreme Court will deny Virginia’s request for a stay. But given how saturated right-wing media is with claims of non-citizens voting, it wouldn’t shock me if such a denouement at the Supreme Court came over at least one or two public dissents. Of course, whether or not 1600 voters will be restored to the rolls may not seem like a big deal in a state in which the presidential race isn’t likely to be that close, but this is the same Virginia in which a state legislative race—and control of the House of Delegates—was settled by a drawing after a literal tie in 2017.

Mississippi: The Fifth Circuit Drops a Bomb

And then there’s the Fifth Circuit—which, in a case out of Mississippi, held late Friday that federal law bars all states from counting any mail-in or other absentee ballots unless they are received by Election Day. The ruling by the three-judge panel (Ho, Duncan, and Oldham) is nuts on its face (or, to quote UCLA Law Professor Rick Hasen, “bonkers”). That federal law fixes a date for elections does not thereby fix a date on which all votes must be cast (or else all early voting and mail-in voting would be unlawful). And even if it does fix a date by which all votes must be cast, it doesn’t remotely follow that the relevant deadline is when the vote is received—since the relevant act from the perspective of the person casting a ballot is the submission of the ballot, i.e., depositing it into a mailbox. Indeed, its rulings like this that are part of why the Fifth Circuit has developed such a … reputation.

The good news, such as it is, is that the ruling is, for now, almost certainly toothless. The panel specifically declined to order any particular remedy (perhaps because it knew that even the thinnest application of Purcell would require immediately freezing such a remedy). Instead, it remanded the case to the district court to decide what the remedy ought to be. And that remand won’t even become effective until the mandate issues—which may not be for quite some time if any of the affected parties seek rehearing en banc or Supreme Court review, which sure seems likely. Thus, even in Mississippi (the one state directly implicated by the ruling), mail-in ballots that arrive after Election Day will still likely be counted. Of course, if it turns out that there’s a federal election in Mississippi that turns on whether mail-in ballots arriving after Election Day should be counted, the Fifth Circuit could well step back in at that point. But the closest of Mississippi’s four U.S. House seats in 2022 was 60-40, with a margin of 36,401 votes (thanks, gerrymandering!); and something tells me that Senator Wicker’s margin in his re-election to the Senate won’t be even that close (let alone former President Trump’s margin in the state).

But whereas that “good news” helps to explain why it’s unlikely the Supreme Court will be dragged into this dispute this week or next, it is very likely that the Court will have to take up this case at some point—not because of its effects on the 2024 election, but because of the bigger, forward-looking question of whether federal law really does bar states from counting any remote votes that arrive after Election Day (besides Mississippi, 17 other states and the District of Columbia currently do so). In the meantime, the Fifth Circuit ruling will also provide fodder (to anyone looking for it) for claims of mischief if the margins are very close in any states that count such ballots. Indeed, especially because it’s almost certainly not going to have any effect in this cycle, it makes you wonder why the panel didn’t just hold off on issuing its ruling until after the dust had settled. Then again, it’s the Fifth Circuit.

***

To be sure, these are hardly the only election-related disputes out there. But my own subjective assessment is that these are the cases receiving the most national attention—and, with the exception of the Mississippi case, the ones most likely to make it to the Supreme Court this week. A lot can change in a short period of time, of course. And there will quite likely be more litigation once states start reporting results. But if this is where things stand eight days out, perhaps we can be cautiously optimistic that, at least as of now, the justices won’t be asked/be able/have to play a central role in the upcoming election.

Fingers crossed.

SCOTUS Trivia: Joining the Court, by Month

Yesterday marked the fourth anniversary of Justice Barrett’s swearing in—after Justice Thomas last week became just the tenth justice to mark his 33rd anniversary on the Court. That got me thinking about the question of when, over the Court’s history, the most justices have ascended the bench. Even with Justices Barrett and Thomas, it turns out that October is only the second-most common month for when justices joined the Court, with 21 (out of 121 total = 116 justices, plus five associate justices who received second appointments as Chief Justice). The most common month, historically, has actually been January, during which 24 justices began their terms (including, most recently, Justice Alito in 2006).

As for the least-common month, that “honor” goes to November—and it’s not even close. Only Bushrod Washington (in 1798) and Gabriel Duvall (in 1811) were sworn in in November. There are lots of reasons for November’s infrequency, some of which have to do with when the Court’s term has begun historically, and some of which may relate to the disruptive political effects of … Election Day (how’s that for a hook!). Either way, though, it wouldn’t have been my first guess before I sat down to look. (My guess, FWIW, was what turns out to be the second-least-common month—July, during which five justices have joined the Court.)

This couldn’t be less important—but that’s why it’s trivia.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next week.

Happy Monday, y’all; I hope you have a great week! And if you haven’t already voted or made a plan for how you’re going to, please, please do so.

By “pending,” I mean “formally docketed with the Court.” It’s possible the Virginia or Pennsylvania applications described below will have been submitted to the Court by the time this newsletter goes out, but they won’t have been docketed.

The efforts of some judges or legislators to deprive people of the liberty of voting or the power of their votes remind me of some of the finer points of Citizens United.

In our “republic” clearly “the people are sovereign.” Citizens United also quoted an earlier dissenting opinion by Justice Douglas, who was joined by Chief Justice Warren and Justice Black: “Under our Constitution it is We The People who are sovereign. The people have the final say. [Public officials] are their spokesmen. The people determine through their votes the destiny of the nation.”

So in Citizens United, SCOTUS emphasized that our powers as sovereigns necessarily included “the ability of the citizenry to make informed choices” about many public servants and public issues. This "ability" is "essential.” “Political speech” (including voting) is “indispensable to decisionmaking in a democracy” by citizens who are sovereign. “The Constitution” clearly “confers upon voters,” (it is more accurate to say the Constitution secures to voters as sovereigns) the “power to choose” (directly or indirectly) some of our public servants.

“Speech” (including voting) “is an essential mechanism of democracy” as a “means to hold officials accountable to the people.” “The right of citizens to inquire, to hear, to speak, and to use information” (including by voting) is essential “to enlightened self-government and a necessary means to protect it.” The power of enlightened self-government is synonymous with sovereignty. Thinking and speaking about government is the primary purpose and duty of government. It also is the primary power of sovereignty.

“Political speech” (especially voting) is “indispensable to decisionmaking in a democracy.” Voters’ decisions “are integral to the operation of the system of government established by our Constitution.” Any purported “law” that would deprive sovereign citizens of the liberty or the power of voting clearly “must comply with the First Amendment; and, it is our law and our tradition that more speech, not less, is the governing rule.”

“Premised on mistrust of governmental power, the First Amendment stands against attempts to disfavor certain subjects or viewpoints.” “Prohibited, too, are restrictions distinguishing among different speakers, allowing speech by some but not others.” “As instruments to censor, these categories are interrelated: Speech restrictions based on the identity of the speaker are all too often simply a means to control content.” “The First Amendment protects speech and speaker, and the ideas that flow from each.” So “the First Amendment generally prohibits the suppression of political speech based on the speaker’s identity.”

“For” the “reasons,” stated above, “political speech” (including the liberty and power to vote) “must prevail against laws that would suppress it, whether by design or inadvertence. Laws that burden political speech are ‘subject to strict scrutiny,’ which requires the Government to prove” two important points: first, that “the restriction” actually does support a legitimate “interest” that is “compelling,” and, second, that “the restriction” is “narrowly tailored to achieve that [compelling] interest.”

Montesquieu, too, emphasized the nexus between sovereignty and suffrage. In The Spirit of the Laws he highlighted the spirit of sovereignty:

“In a democracy the people are in some respects the sovereign, and in others [the people are] the subject," i.e., of the laws they create. The primary “exercise of sovereignty” in a democracy is by citizens “by their suffrages.” Suffrage is the speech of sovereigns.

The plain text of our Constitution establishes who is sovereign in America: essentially every “citizen” (Amendment XIV, Section 1) who has the right and the power to vote (Amendment XIV (Section 2); Amendments XV, XIX, XXIV, XXVI). "The sovereign people" of America essentially include all citizens regardless of creed, color, race, sex, wealth or age (after 17). Our public servants should (and should be required to) respect our sovereignty. They should not be permitted to undermine it by obsessing over interests that clearly are not compelling.