104: Relisting, Rescheduling, and Two Long-Pending Capital Cases

Two long-pending cert. petitions in capital cases help to illustrate the two different ways in which the justices put off decisions respecting whether or not to take up a new case

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

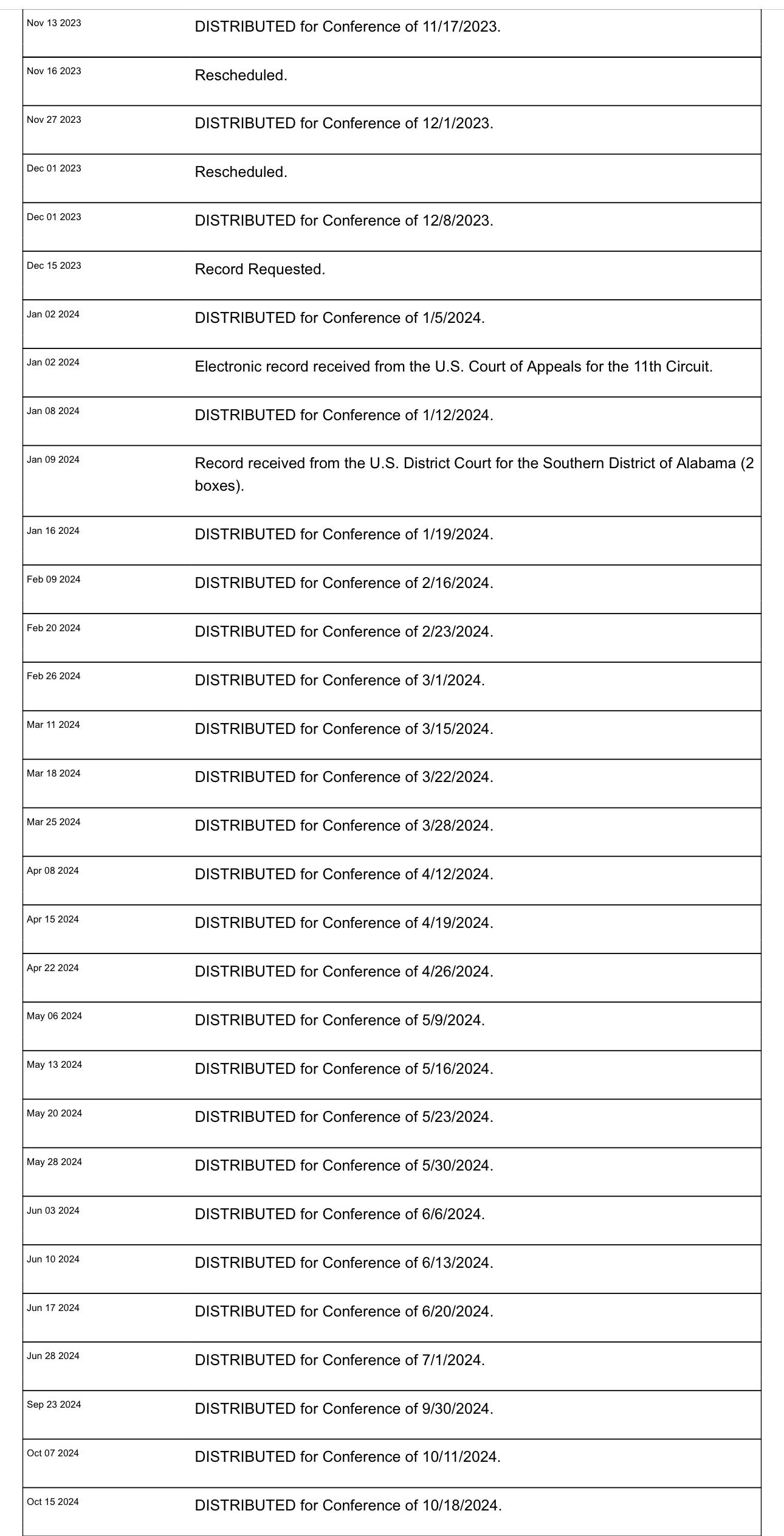

I’ve been meaning for some time to write about “relisting” and “rescheduling”—the two (almost entirely obscure) mechanisms that the justices use to put off deciding whether or not to take up a new appeal. It turns out that, at least as of this morning, there are two cert. petitions in capital cases that have been pending for … a very long time, both of which help to illustrate these mechanisms—and how difficult it is for anyone on the outside to figure out why the justices are unwilling to publicly resolve whether to take the case or not. Indeed, Hamm v. Smith was first distributed for the justices’ Conference on October 27, 2023. And Andrew v. White was first distributed for the justices’ March 28, 2024 Conference. We may never know why it’s taken so long, but both cases provide useful examples of how even the timing of the cert. process is guided by a lot of strategic and tactical behavior by the justices—to which we are almost never privy, even after the fact. Here, for instance, are the last 31 docket entries in Hamm:

But first, the news.

On the Docket

Last week brought with it the first two opinions of the Court’s October 2024 Term—although both were just separate writings respecting denials of emergency relief. I’ve written already (for last Thursday’s bonus issue) about Justice Kavanaugh’s statement respecting the denials of stays in the eight applications consolidated in West Virginia v. EPA. And the other was Justice Sotomayor’s 10-page statement on Thursday respecting the denial of a stay of execution in the case of Texas death-row prisoner Robert Leslie Roberson II (whose execution was stayed later on Thursday night by the Texas Supreme Court). Other than those two orders and last Monday’s regular Order List (which included no new grants of certiorari and no separate writing), that was it for rulings from the Court last week.

The Court also released its argument calendar for the December 2024 session. Two things of especial note: First, the argument in Skrmetti (the major case about transgender discrimination) has been set for Wednesday, December 4. Second, despite having room for 12 arguments, the Court has scheduled only eight—perhaps a reflection of how behind the justices have been in filling out their OT2024 calendar (and, more generally, of how many fewer cases the Court is hearing every term these days).

The justices are off the bench this week—having concluded the October argument session last Wednesday. We expect a regular Order List this morning at 9:30 ET, but nothing else is “due.” There are some pending emergency applications that the justices might resolve this week, but as ever, there’s no way to predict in advance which ones will or will not come down. Otherwise, the Court won’t be back in session until two weeks from today—also the next time, after today, that we expect orders.

The One First “Long Read”:

Relisting, Rescheduling, Hamm, and Andrew

One of the most inscrutable aspects of the certiorari process is the justices’ timing in deciding when to decide (or, at least, to publicly announce) whether to take up a new appeal. It’s fairly common knowledge that, once a “cert. petition” has been fully briefed, it is “distributed” for one of the justices’ upcoming Conferences—after which, at some point, the Court issues an order granting or denying review. And the overwhelming majority of cert. petitions are not only denied; they are denied in the very first Order List after the Conference for which they had been scheduled (usually because they weren’t even discussed).

But there’s a subset of cases in which the justices do one of two other things once a case has been distributed for Conference. The first is to “reschedule” the petition for a future Conference; the second is to “relist” the petition after the Conference at which it was at least putatively discussed. If a petition is “rescheduled,” that means that it is removed from the Conference list prior to the justices’ in-person meeting—so that there is no discussion or vote. So far as we know (and this may well be wrong), any justice can request that a petition be rescheduled—and will often ask to do so either to buy time to become more familiar with the dispute or persuade their colleagues of their views; to align the timing of the appeal with other pending cases raising the same or similar issues; or to otherwise put off even a discussion of the matter.

If a petition is “relisted,” in contrast, that could mean one of at least five different things:

The justices did not finish discussing the petition, and so are planning to continue discussing it at the next Conference (for obvious reasons, it’s rare for this to happen more than once);

The justices voted to deny the petition, and one (or more) justices are preparing separate writings respecting the denial (in which case, the petition will continue to be relisted after each Conference until it is denied);

The justices voted to grant the petition, and are taking an extra week to make sure there are no procedural traps or other landmines in the case (this appears to have become the norm since 2014 for just about every grant of certiorari other than those coming from the Long Conference—which is why John Elwood’s “Relist Watch” column has become a good predictor of possible grants);

The justices voted to grant the petition and resolve the case summarily, so the petition gets “relisted” until an unsigned majority opinion is ready to be filed; or

The justices voted to grant the petition, and are deliberately delaying when to make that decision public—perhaps to put the case off until the next term (we know, thanks to Jodi Kantor’s and Adam Liptak’s reporting, that this is exactly what happened in Dobbs).

As you might imagine from the above, although rescheduling and relisting are both relatively common, the greater the number of times a single petition gets rescheduled or relisted, the rarer it is—and the more likely something strange is going on behind the scenes. Dobbs, for instance, was relisted 12 times after the justices voted to grant certiorari. (Masterpiece Cakeshop was relisted 14 times before it was granted at the very end of the October 2016 Term).

Against that backdrop, consider the strange sagas of Hamm v. Smith and Andrew v. White. Hamm involves Alabama death-row prisoner Joseph Clifton Smith. After an earlier reversal by the Eleventh Circuit, the district court held that Clifton was intellectually disabled—so that his execution would violate the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments as interpreted by the Supreme Court in Atkins v. Virginia and Hall v. Florida. The Eleventh Circuit affirmed, and Alabama sought Supreme Court review—arguing not only that the Eleventh Circuit misapplied Atkins and Hall, but that, insofar as they didn’t, those two precedents (from 2002 and 2014, respectively) should be overruled. On the latter claim, Alabama’s petition, with support from an amicus brief on behalf of 14 other states, asks the Court to revisit not just those two cases, but the entire analytical underpinnings of its modern Eighth Amendment jurisprudence—which, since the 1950s, has measured contemporary punishments against “evolving standards of decency,” as opposed to Founding-era understandings, in deciding whether they violate the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause.

The petition in Hamm was docketed on August 21, 2023. It was first distributed for the justices’ Conference on October 27, 2023. And after being rescheduled five times, it has been relisted after each of the justices’ last 22(!) conferences. I had thought that we might be heading for a whole lot of (angry) writing respecting a denial at the very end of the last term—or, at worst, as part of the first Order List from this term. Instead, it’s been relisted two more times since the OT2024 Long Conference. At this point, I have absolutely no idea why this case is still pending. If the Court was going to grant certiorari after a long internal debate, I would’ve expected that order no later than as part of the July 2 “clean up” orders. If the Court was going to deny over a long dissent, I would’ve expected that order no later than as part of the Long Conference Order List on October 7. So… your guess is as good as mine. But the one thing I can say with some confidence is that 22 relists is as many as in any case I can remember—so clearly, something is up behind the scenes.1

And then there’s the even stranger case of Brenda Andrew—the only woman currently on Oklahoma’s death row. Andrew was convicted of murdering her estranged husband in a trial in which prosecutors made much out of her sexual history; played up sex-based stereotypes; and otherwise relied on a host of theories that were inconsistent with the conviction of her co-defendant James Pavatt—who confessed to plotting and committing the murder without her. A divided panel of the Tenth Circuit denied her petition for post-conviction habeas relief—over a dissent from Judge Bacharach that highlighted a “slew of errors” affecting “the fundamental fairness” of the conviction. Andrew’s petition was docketed in January—and first distributed for the justices’ Conference on March 28. Since then, it was rescheduled 11 times, after which the record was requested from the district court and Tenth Circuit. Those were received in July, but the petition was relisted after both the Long Conference and the justices’ October 11 Conference. In other words, in another case in which I would’ve expected some movement by the first Order List of the new term, the justices are … still waiting (and, perhaps, still debating) what to do.2

The legal issues in the two cases have very little to do with each other, so it’s hard to imagine that the timing here is more than a coincidence. It’s also possible, in Andrew, that the 11 reschedules reflected an effort by justices lacking a fourth vote for certiorari to try to persuade a colleague to come onboard—and that this effort has now failed (had it succeeded, we presumably would know by now, since a statement respecting a grant of certiorari is highly unlikely), with a dissent from a denial of certiorari forthcoming. But the 22 relists in Hamm are simply mind-boggling—and, if nothing else, underscore, yet again, just how much discretion is baked into the certiorari process, and just how much strategic and tactical behavior that discretion begets inside the Court as well as outside of it.

Perhaps we’ll know more about one or both cases later this morning. But perhaps we won’t. And either way, we’ll probably never know the full story of why they each took so long—at least not until decades from now, when the current justices’ private papers become publicly accessible.

SCOTUS Trivia: 33 Years for Justice Thomas

This Wednesday, October 23, marks the thirty-third anniversary of Justice Thomas’s swearing-in. Thomas will become the tenth justice to hit that milestone. Only five justices made it to their thirty-fourth anniversary—Douglas, Field, Stevens, (John) Marshall, and Black. And only one made it to 35 (and 36).

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday.

Happy Monday, y’all; I hope you have a great week!

By way of disclosure, I should note that I joined an amicus brief by habeas scholars in support of Andrew’s petition. Just to be clear, the views expressed in this post are mine alone, and do not necessarily represent the views of my fellow amici or our counsel.

I greatly appreciate your analysis and insight, Steve. You invited ideas for future topics, so here goes.

In anticipation of Chutkan's case ending up back in the S CT, could you help prepare us? First, are official acts on the "outer perimeter" synonymous with "implied powers"? Second, explain presumption. Who has the burden? Smith rebuts the presumption of immunity; then, Trump rebuts the rebuttal? Third, how can any conduct by a President be "official" if, by virtue of its illegality, it is a failure to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed" (eg, ordering a Navy Seal to kill a political rival)? Fourth, historically, the law recognizes qualified immunity for government officials (right?). So is the ruling the president has absolute criminal immunity for core duties unprecedented in law, or unprecedented vis a vis the U.S. President, or both? Fifth, the Court said (Art II s 1) the executive power is vested in one person (the President). Is it significant that the opinion also refers to Executive "Branch," thereby clouding Smith's argument surrounding the Trump-Pence conversations about Pence's President-of-the-Senate role? Thanks.

To what do I attribute Thomas's longevity? He takes care of himself by doing just about anything that makes HIM happy. Must admit I'm trying the same strategy myself.