103. Alien Enemies in the Supreme Court

Setting the record straight on the 1798 statute former President Trump claims he'll use to summarily arrest and deport undocumented immigrants—and the Supreme Court's handful of interactions with it

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

Despite a busy week of Court-related news, I wanted to use today’s post to provide some context for a claim former President Trump has started making on the campaign trail—that, if elected, he’ll use the Alien Enemy Act of 17981 to summarily arrest and deport undocumented immigrants. Trump’s critics have condemned the proposal at least in part by claiming that the 1798 statute was the basis for the Japanese American internment camps during the Second World War. In this week’s “Long Read,” I aim to (1) explain why that’s not true; (2) summarize what little the Supreme Court has said about the act; and (3) explain why, in light of (2), this is almost certainly empty (if nevertheless disturbing) posturing by former President Trump.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

The first official week of the October 2024 Term was a busy one at the Court—albeit not as busy as I had expected. Monday’s regular Order List didn’t make a ton of news (I was most surprised by both the denial of certiorari in the Texas EMTALA/emergency abortion case and the lack of public dissents therefrom). Indeed, there were no separate writings respecting any of Monday’s orders; and the Court didn’t add any additional new cases to the docket either Monday or later in the week. We also didn’t get any rulings on any of the pending emergency applications—so we’re still waiting on those, too. Instead, the real focus of energy last week was the first oral arguments of the term—about which I’ll hope to have a bit more to say in a future issue.

Turning to this week, the justices are off today for the federal holiday. But they’ll be back on the bench at 10 ET tomorrow for the second week of October arguments, and we expect a substantial Order List at 9:30 ET tomorrow—including perhaps a bunch of additional grants of certiorari, adding more cases to the docket for later this term. (For a preview of what might be coming, check out John Elwood’s indispensable “Relist Watch” column over at SCOTUSblog.) Presumably, at some point, the Court is going to have do something with the emergency applications in the power-plant emissions cases. The justices will also soon need to figure out which of the numerous pending cases about Congress’s power to delegate authority to private actors they’re going to take up (there’s an administrative stay in place in one of them). But at least to this point, the Court doesn’t seem to be in much of a hurry in either set of disputes.

The One First “Long Read”:

The Alien Enemy Act of 1798

As noted above, former President Trump’s increasingly dark turn on immigration issues led him on Friday to suggest that, if elected, he would use the Alien Enemy Act of 1798 to summarily arrest and deport undocumented immigrants in the United States. Among the criticisms Trump’s proposal provoked were claims that the same statute had formed the basis for the Japanese American internment camps during the Second World War—as implicitly sustained by the Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States (which was argued exactly 80 years ago this past weekend).

Way back when I was a brand-new law professor, I wrote a whole (well, half of an) article about the Alien Enemy Act—so it seemed that it might be useful to provide some background on the statute, on how (for nefarious reasons) it had nothing to do with the Japanese American internment camps, and on how what little the Supreme Court has said about the statute ought to pour cold water on it being used the way that Trump appears to be contemplating.

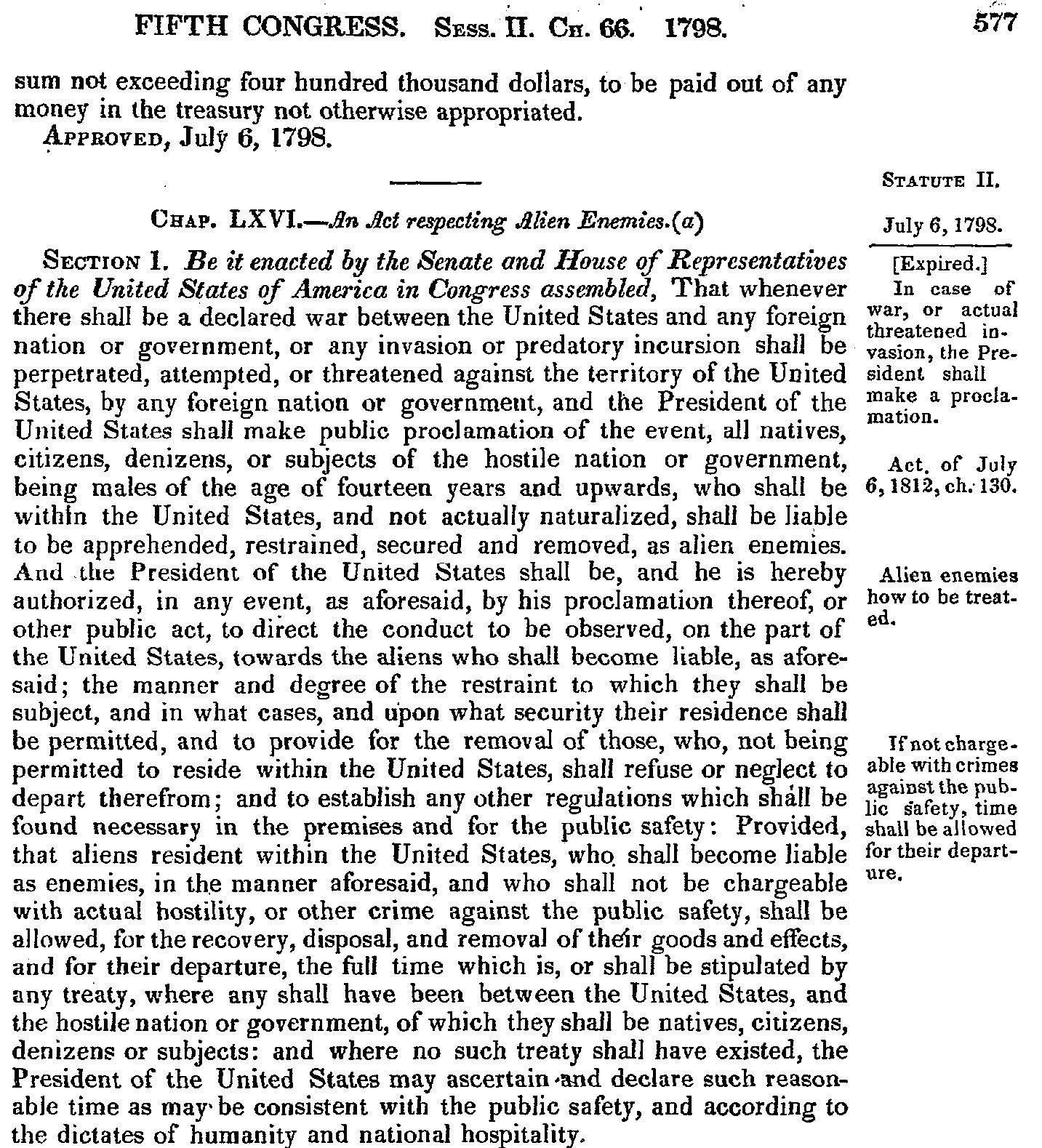

As J. Gregory Sidak has written, “The Alien Enemy Act was enacted on July 6, 1798, eleven days after Congress enacted the notorious Alien Act and eight days before it enacted the even more infamous Sedition Act.” Passed during the “quasi-war” with France, the Act was meant to give the President broad authority over potential spies and saboteurs at home during a conflict overseas. Specifically, the significant grant of power came in section 1:

[W]henever there shall be a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion shall be perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States, . . . all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government, being males of the age of fourteen years and upwards, who shall be within the United States, and not actually naturalized, shall be liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and removed, as alien enemies.

The President's authority under section 1 was sweeping, but the Act explicitly provided for judicial review, allowing a “full examination and hearing” into whether “sufficient cause . . . appear[ed]” to conclude that the individual was actually an “alien enem[y].” Thus, the text of the Act itself explicitly suggested that judicial review was always available to review whether an alleged “enemy alien” actually fell within the Act’s purview. As clarified by Justice Bushrod Washington on circuit in the landmark early case of Lockington v. Smith, however, a court order was not a mandatory prerequisite to the executive detention of an alien enemy; judicial review need only be available subsequent to incarceration. (There’s also a significant War of 1812-era ruling on circuit by Chief Justice Marshall, which was unearthed in the 2000s by Gerry Neuman and Charles Hobson, and which, among other things, stresses the significance of judicial review under the statute.)

Because the act requires a declaration of war (or an “invasion or predatory incursion”), it remained all-but dormant between the War of 1812 and the First World War. But there are a number of reported cases during the latter conflict in which the pattern of judicial review that emerged was focused on whether the individual in question fell within the statute’s definitional scope—i.e., whether they were “natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of” a country against which Congress had declared war. If the answer was yes, the courts typically held there was little more for them to do. But there was robust review of what might be viewed as the “jurisdictional” fact of the detainee’s citizenship—of what country they were affiliated with, and whether Congress had declared war against that country.

Indeed, a declaration of war was more than just a formality; as courts were confronted with hundreds of cases during the Second World War, their review focused extensively on the applicability of the jurisdictional facts, including whether the detainee was connected to a country against which the United States had declared war, and exactly when they were so connected (and when they were arrested). Again and again, lower courts, at least, took a narrow and formalistic approach to when (and to whom) the statute could apply even if they accepted that their role was limited in cases in which the statute’s applicability was clear.

That might help to explain why, when it came to Japanese American internment, the Roosevelt administration did not rely upon the Alien Enemy Act of 1798. Even if first-generation Japanese nationals resident in the United States (issei) could be detained under the auspices of the act, there was no argument that the act could extend to U.S. citizens of Japanese descent (nisei)—for the simple fact that they weren’t “natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects” of Japan. Indeed, as Chief Justice Rehnquist pointed out in his book on civil liberties during wartime, All the Laws But One, had the federal government relied on the Alien Enemy Act and detained only issei (like the scores of German and Italian nationals who were detained under the Alien Enemy Act during the war), it’s quite possible that we would look back far less harshly on the World War II-era internment policy.

Instead, there was no statutory authority for most of the internment policy; the statute the Supreme Court upheld in Korematsu merely made it a crime to violate an exclusion order; it didn’t affirmatively authorize the exclusion. (I’ve written before about the Court’s forgotten companion ruling to Korematsu, Ex parte Endo, which rested on this precise distinction in granting habeas relief to an internee who had not violated an exclusion order.) Thus, not only is it incorrect to claim that the Alien Enemy Act authorized the internment camps, but perhaps the biggest reason why the camps were so legally (and not just morally) odious is because they deliberately went beyond the more limited authority that the 1798 statute would have provided—and that the federal government used with respect to German and Italian nationals in the United States.

The Supreme Court finally considered the validity of long-term detention under the Alien Enemy Act in 1948—in Ludecke v. Watkins. In Ludecke, a 5-4 majority rejected a due process challenge to detention under the act, even where, as in that case, the detainee was a German national still being held more than three years after Germany’s unconditional surrender. Ludecke held that, for purposes of the Alien Enemy Act, the question of when the war Congress had declared actually ended was up to the political branches—a political question not to be second-guessed by the courts. (Another one of my early-career articles was about Ludecke, and what it portended for the war against al Qaeda that Congress authorized in 2001.) And it reinforced that judicial review under the act was limited to the question of whether the act had properly been invoked against the detainee—including the country of which they were a citizen and whether the United States was in a declared war with that country (which, again, was a matter the Court—controversially—left to Congress and the President).

But in the process, Ludecke reinforced the idea that courts should still play some role in cases arising under the act—at least in enforcing its jurisdictional limits. That’s significant, in my view, because it raises two serious problems with the specter former President Trump is evoking—of using the act for summary (i.e., extrajudicial) arrests and deportation, and of relying upon the “invasion or predatory incursion” language (since we, obviously, are not currently in any declared wars).

First, even in the middle of the First and Second World Wars, courts were still open to review claims by those detained under the act who challenged whether they were properly within the statute’s scope. Second, and relatedly, although there is no case law about the “invasion or predatory incursion” language, the cases that are out there all tend to read the statute to require that a specific country be identified as the aggressor. Whatever one thinks about the situation along the U.S.-Mexico border, it can hardly be said with a straight face that citizens of a single, foreign country are engaged in a coordinated “invasion or predatory incursion.” That spells real trouble for if and when courts get their hands on habeas petitions by anyone arrested and detained under the act.

Indeed, if this were really a policy debate, there are already plenty of authorities that allow for the arrest and detention (pending removal) of those non-citizens without legal authorization to be in the United States. The issue, at least in recent years, has not been legal authorities; it has been the capacity of the federal government to actually seek out and arrest those who are legally subject to arrest and removal. Relying on an old statute won’t help solve the resources problem. And if the above analysis means anything, it also suggests that the old statute wouldn’t provide a way around judicial review, either. Instead, it seems designed more to appear to be a solution than to be an actual solution—one that has stirred up understandable, if misplaced, comparisons to prior mass detention efforts by the federal government. One suspects it won’t be the last time we hear about this statute—or other plans to rely upon similarly ill-fitting old statutes.

SCOTUS Trivia: So When Did World War II “End”?

Although the Supreme Court in Ludecke held that the United States was still at war with Germany in June 1948 (at least for purposes of the Alien Enemy Act), the Court would have a chance, in another Alien Enemy Act case, to clarify exactly when the war (at least against Germany) had “ended.”

Specifically, in United States ex rel. Jaegeler v. Carusi, in January 1952, the Court held that the authority provided by the Alien Enemy Act had expired with respect to Germany on October 19, 1951—when Congress, through a joint resolution, formally terminated the war with Germany. And although the government hadn’t used the Alien Enemy Act with respect to Japan, that war formally ended on April 28, 1952—the date on which the peace treaty with Japan became effective.

It turns out that “when do wars end” is a much more complicated question legally than it is in the real world. To take just one example, even the Civil War has two answers—one for Texas (August 20, 1866), and one for everywhere else (April 2, 1866).

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday.

Happy Monday, y’all; I hope you have a great week!

Former President Trump (and most of the coverage of his remarks) has referred to the statute as the Alien Enemies Act. At least historically (and in the handful of Supreme Court decisions to discuss it), the more common name for the statute has been the singular “Alien Enemy Act,” and that’s what I use here.

Japanese immigrants are issei (is- abbreviation of ishi, 1, -sei generation); their second-generation US citizen children are nisei (ni-, 2).

Your column is very interesting, as usual, but I think you got the definitions of issei and nisei backwards. Issei are first-generation Japanese nationals who came to the U.S., while nisei are the second generation who were born as U.S. citizens.