102. Setting the Table for the October 2024 Term

The new term opens without any of the blockbuster cases that have characterized recent sessions, but with the shadow of the election looming large over the Court's docket—and its future

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

With the October 2024 Term beginning today, the subject of this week’s “Long Read” is an obvious one: an effort to take a more holistic look at what we expect from the Court not just between now and June, but over the next 52 weeks—until Monday, October 6, 2025. Some of that is necessarily a fool’s errand; the Court still has probably around 1/3 of its docket to fill when it comes to cases to be argued and decided this term, and it’s a virtual certainty that at least some of those cases aren’t even on our radars yet (to say nothing of potential emergencies that might arise over the next 12 months).

But even with that uncertainty, it seems pretty obvious that the election is going to be one of the major themes of the term to come—not just because of the chance that it ends up being affected (if not decided) by the Court, but because of how the outcome will bear not just on the work of the Court (or its composition) going forward, but on the Court’s broader institutional role in the years and decades to come. That, and the Fifth Circuit is once again going to play an outsized role in a lot of what the Court does this term.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

The First Monday (and official opening) of the Supreme Court’s October 2024 Term brings with it a flurry of developments from the Court—most expected, but a few that were not.

Starting with last week, on Tuesday, the Court issued a trio of unsigned, unexplained orders denying stays of execution to Texas death-row prisoner Garcia White. The Court also ended the week (and the October 2023 Term) with two unsigned, unexplained rulings on Friday—rejecting, without public dissent, two of the three sets of applications challenging new EPA rules. (The denials were of the challenges to the new methane and mercury standards; the eight even more important challenges to the new power-plant emissions rules filed back in July remain pending.) For those scoring at home, that brings the total number of full Court rulings on emergency applications for OT2023 to 122(!) That’s the most, by quite a fair margin, since I’ve been tracking the total (OT2022’s total, for comparison, was 76, and OT2021’s total was 72.)

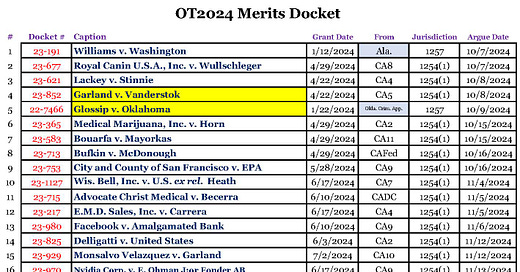

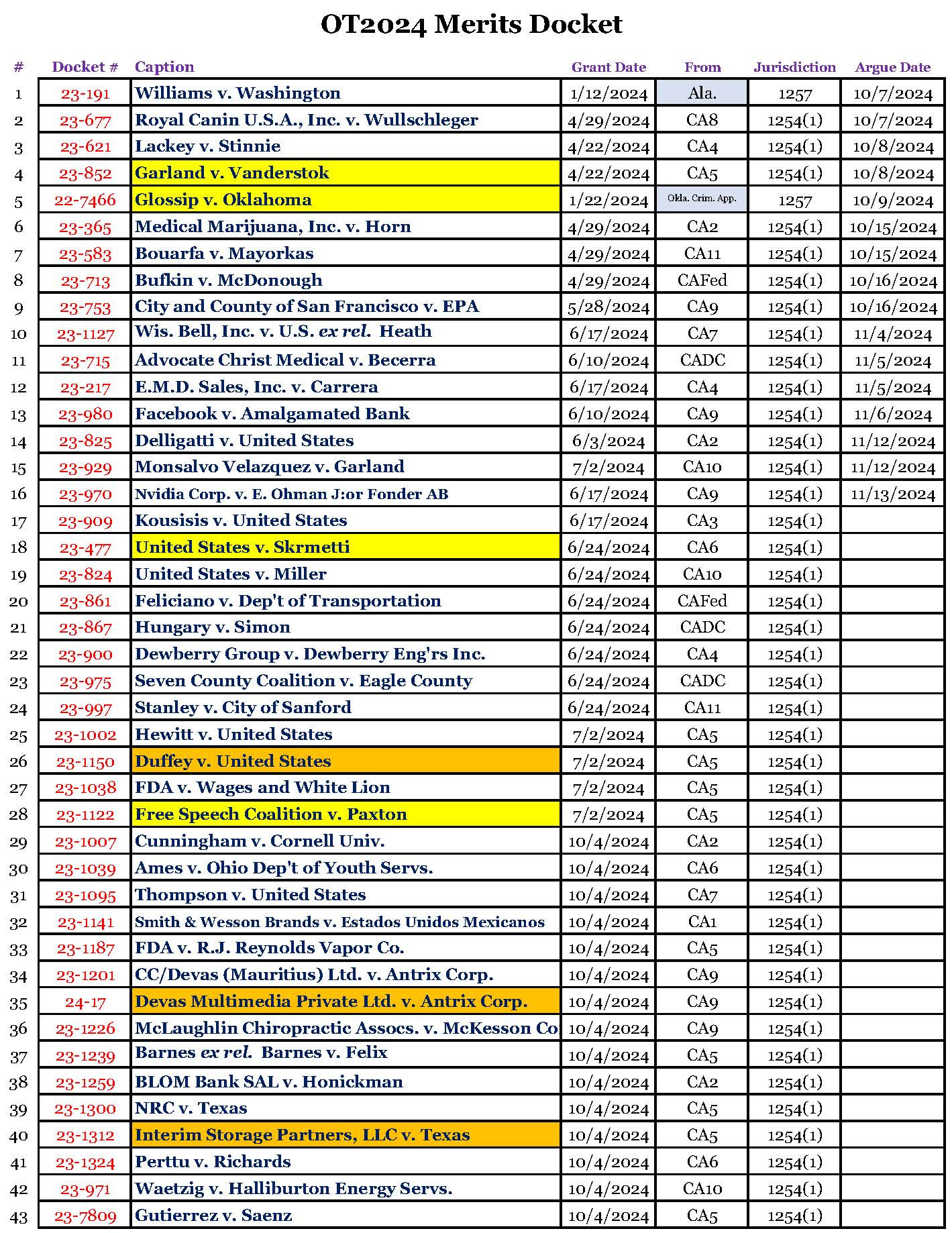

The biggest news from Friday, though, were the (expected) grants of certiorari coming out of the Long Conference. In all, the justices added 13 cases to the docket for the new term—bringing the total (counting pairs of consolidated cases as one each) to 40. There are a lot of interesting legal questions among the 13 new grants, but no blockbusters. Among others, the Court agreed to hear an effort by gun manufacturers to toss a lawsuit by the government of Mexico (which seeks to hold the manufacturers liable for the consequences of the trafficking of their products in Mexico); a pair of cases about whether the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has the authority to provide for the temporary disposition of low-level radioactive waste (a quietly important fight about the major questions doctrine); a capital case out of Texas in which the Court has already stayed the petitioner’s execution; and a Fourth Amendment case(!!) about the time-frame courts should consider in deciding whether an officer’s use of force was “reasonable.” It’s a good bet that just about all of these cases will be argued in either the January 2025 or February 2025 argument sessions. Here’s the full list of cases pending for argument:

Turning to this week, we expect the longest Order List of the year at 9:30 ET—including denials of certiorari in most of the remaining cases from last week’s Long Conference, and the possibility of some summary rulings (and separate writings), as well. It’s really hard to predict which cases from the Long Conference might provoke separate writings, but the odds are good that at least some of them will.

Then, at 10 ET, the justices will take the bench for the first time since July 1—when Chief Justice Roberts will formally open the Court’s October 2024 Term. The Court will then hear the first two arguments of the Term—one about whether state courts can apply state exhaustion requirements to federal civil rights claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983; and one about whether a plaintiff who files a case in state court can defeat a defendant’s removal to federal court by amending their complaint to eliminate the removable claims. In all, the justices are set to hear a total of five arguments this week—including in the federal government’s appeal in the “ghost guns” case on Tuesday; and in the Glossip v. Oklahoma capital case on Wednesday.

The justices also still have a dozen pending emergency applications to resolve—including the aforementioned power-plant emissions cases. The most significant new application, by South Carolina in a subpoena dispute with Google in an antitrust suit, almost certainly won’t be resolved this week; Chief Justice Roberts called for a response by 4:00 p.m. ET this Friday.

The One First “Long Read”: What Will OT2024 Bring?

At least for now, the October 2024 Term is lacking for the blockbusters that have been so central to the top-line stories of the Court’s recent sessions—Bruen and Dobbs in OT2021; racial preferences, student loans, and religion in OT2022; and … everything (but especially Trump and the administrative state) in OT2023. Retired federal judge Nancy Gertner and I have an op-ed in today’s New York Times suggesting that the “real” blockbuster of the term is the Court itself—and the extent to which public faith in the Court as an institution continues to erode, with increasingly ominous long-term implications. As we explain,

. . . A court that loses its institutional credibility is a court that will be powerless when it matters most.

It isn’t hard to imagine a future President Trump, returned to the Oval Office perhaps with the court’s help, thumbing his nose at the justices should they have the temerity to rule against his policies, as they often did during his first term. (For example, if the Supreme Court rules that some future executive order is unconstitutional, Mr. Trump could nevertheless order law enforcement or administrative agencies to implement it.) Defying the Supreme Court wasn’t politically possible at that time, nor has it been an option for President Biden even as the court has blocked, or refused to unblock, a dizzying array of his domestic policy programs.

But the Supreme Court of 2024 is not the Supreme Court of 2017, 2018 or even 2020. It is a court that has been willing, even eager, to sweep aside decades of settled law. It overruled Roe v. Wade; ended racial preferences in college admissions; greatly expanded the Second Amendment; and kneecapped the administrative state, all in rulings that divided the justices along partisan lines. It is also a court that ignored calls for the disqualification of justices when there was the appearance, if not the reality, of conflict; and reacted to calls for meaningful ethics reform by adopting an unenforceable Code of Conduct that gives half-measures a bad name.

If Mr. Trump turns against a Supreme Court with a Republican supermajority (as his running mate, JD Vance, has proposed), who would support the court? Mr. Trump’s base? Hardly. Congress, unable to enact real reforms? Critics?

This is why, to me, the election is such an inflection point for the Court. It’s not just the possibility that the Court is going to end up being asked (and agreeing) to resolve cases that might directly affect the outcome of the presidential election; it’s also the certainty that the shape of the Court’s next decade will be directly affected by the election’s results—far more so than the result of the 2020 presidential election. Beyond the possibility that the next President may have the opportunity to appoint new justices (at least so long as the same party controls the Senate), there’s also the very different oversight of the Court we might see from the House Judiciary Committee, armed with subpoena powers, if Democrats re-take control of the House of Representatives. Beyond the alarming specter Judge Gertner and I evoked in our op-ed of a second-term President Trump defying an adverse ruling, there’s also the very different (but also troubling) possibility of a Court that blocks most, if not all, of the key pieces of a President Harris’s domestic policy agenda. And in both scenarios, there’s the continuing conversation surrounding meaningful Court reform—or, at least, the continuing public discourse about the extent to which the Court ought to be reformed. The more that the Court is in the spotlight, the more that it’s likely to continue provoking public discussions about what it’s actually doing—and whether the pattern of the last few decades, in which Congress has largely left the justices to do … whatever they want … is in the long-term interests of the health of our constitutional system.

Of course, one of the ways for the justices to lower the temperature is to keep their head down over the next 52 weeks—to try to stay out of election-related disputes as much as possible; to try to avoid dividing along the most obvious political and ideological lines in those election-related cases that they have to take up (and in other especially high-profile disputes); and to find ways, both through their decisions and otherwise, to repeatedly demonstrate how the Court is more than just a font for the exercise of partisan political power. In that respect, the absence of a slew of blockbuster, ideologically charged cases may be a godsend—at least insofar as it provides the Court with the opportunity to appear to be tacking toward the middle. We’ll see how long that lasts, but it has never struck me as a coincidence that public confidence in the Court has eroded at the same time as a greater percentage of the Court’s merits docket has been composed of high-profile, politically (if not socially) divisive disputes.

This may also be where the Fifth Circuit once again looms large. After Friday’s cert. grants, the Fifth Circuit is now responsible for 10 of the 43 cases on the Court’s plenary docket for OT2024—or 23.3%. Even if we discount consolidated cases, it’s still responsible for 20% of the Court’s workload (8/40). To put this into context, the Ninth Circuit (the federal appeals court that hears the most cases, by far) is responsible for 6 of the grants to this point (5 excluding consolidated cases), and no other lower court is responsible for more than 4. Once again, the cases coming from the Fifth Circuit have a rather heavy ideological skew to them; half are appeals brought by the federal government of rulings against federal policies, and at least three of the others involve circuit splits in which the Fifth Circuit is … to the right … of other courts of appeals.

And, although it’s impossible to say for sure, my own crude math (and poor predictive skills) projects that the Court is likely to take anywhere from 4–8 more cases from the Fifth Circuit just based upon the cert. petitions that are already (or soon will be) pending. If we see another term like the last two, in which the Fifth Circuit is the lower court with the highest number of reversals, perhaps the justices will finally pause to publicly ask why that’s happening, and realize that the answer has a heck of a lot to do with transparent efforts by litigants to move the entire corpus of federal law sharply rightwards. Publicly pushing back against those efforts would be a very welcome sign of the Court’s political independence; continuing to indulge it would be … something else entirely.

This leads to what, in my view, is the real question heading into the Court’s October 2024 Term: Are we going to see more of the same, or is this the term when we start to see meaningful suggestions, in the justices’ individual behavior and the Court’s broader decisionmaking, that there’s at least some sensitivity on the part of a majority of the justices to the erosion of public faith in the Court—and its consequences? At some point, are justices appointed by Republican presidents going to consider the possibility that critics with whose politics they disagree might have a point? Or is the Court going to continue to bury its head in the sand—while its defenders loudly insist that there’s nothing different about today’s Court compared to its predecessors?

There’s a quote I’m reminded of—from a speech that then-D.C. Circuit Judge Warren Burger gave to the Ohio Judicial Conference in September 1968, nine months before he was nominated and confirmed as Chief Justice:

A court which is final and unreviewable needs more careful scrutiny than any other. Unreviewable power is the most likely to self-indulge itself and the least likely to engage in dispassionate self-analysis . . . . In a country like ours, no public institution, or the people who operate it, can be above public debate.

On the first morning of the First Monday, it is far too early to tell if the current Court is going to agree. But at the very least, it’s something we—and the justices themselves—ought to be thinking about as they step in front of the curtains to usher in the new term.

SCOTUS Trivia: The “First” Monday in October

For First Monday 2023, I wrote about the history of the “First Monday in October,” including the historical evolution of the date on which the Supreme Court’s term has officially begun; how Congress finally settled on the “first” Monday in October in 1916—in a statute that went into effect starting on October 1, 1917; and how the quiet shift to a “continuous” term in the 1980s has mooted most of the historical significance of the formal beginning of the Court’s new session.

But even though today marks the 108th time that the Court’s term has begun on the First Monday in October, the tradition of holding oral arguments on the first day of the term is of far-more-recent vintage. Near as I can tell, the practice became regularized only beginning with the October 1975 Term—when the Court heard four(!) arguments on Monday, October 6. The government lawyers appearing before the Court that day included Solicitor General Robert Bork and two future circuit judges—A. Raymond Randolph and Frank Easterbrook. Prior to the mid-1970s, the public session on First Monday tended to be purely administrative (and the justices would instead spend much of the day concluding the work of the Long Conference).

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday.

Happy First Monday, y’all; I hope you have a great week!

Trump is leading not an election campaign, but an insurrectionary movement. The court was “supremely” aware of this when it followed the most corrupt and undemocratic president in well more than a century, with a ruling giving future presidents full immunity for official acts and all the rest. I would love to believe that this court will suddenly see the light (of democracy) and reverse course. But even you have not been able to find an iota of evidence that it will. If Trump doesn’t win through votes, this court’s reactionary majority is there to ensure that he can win “by hook or by crook.”

The Supreme Court showed its true colors last term. The election is a test to see if its illegitimacy will have even a smidgen of pushback or it will be aided and abetted even more.