101. Justice Black and the 1948 Texas Democratic Senate Primary

76 years ago yesterday, Justice Black effectively sealed LBJ's first election to the U.S. Senate by staying lower-court investigations into alleged improprieties in the Texas Democratic primary.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

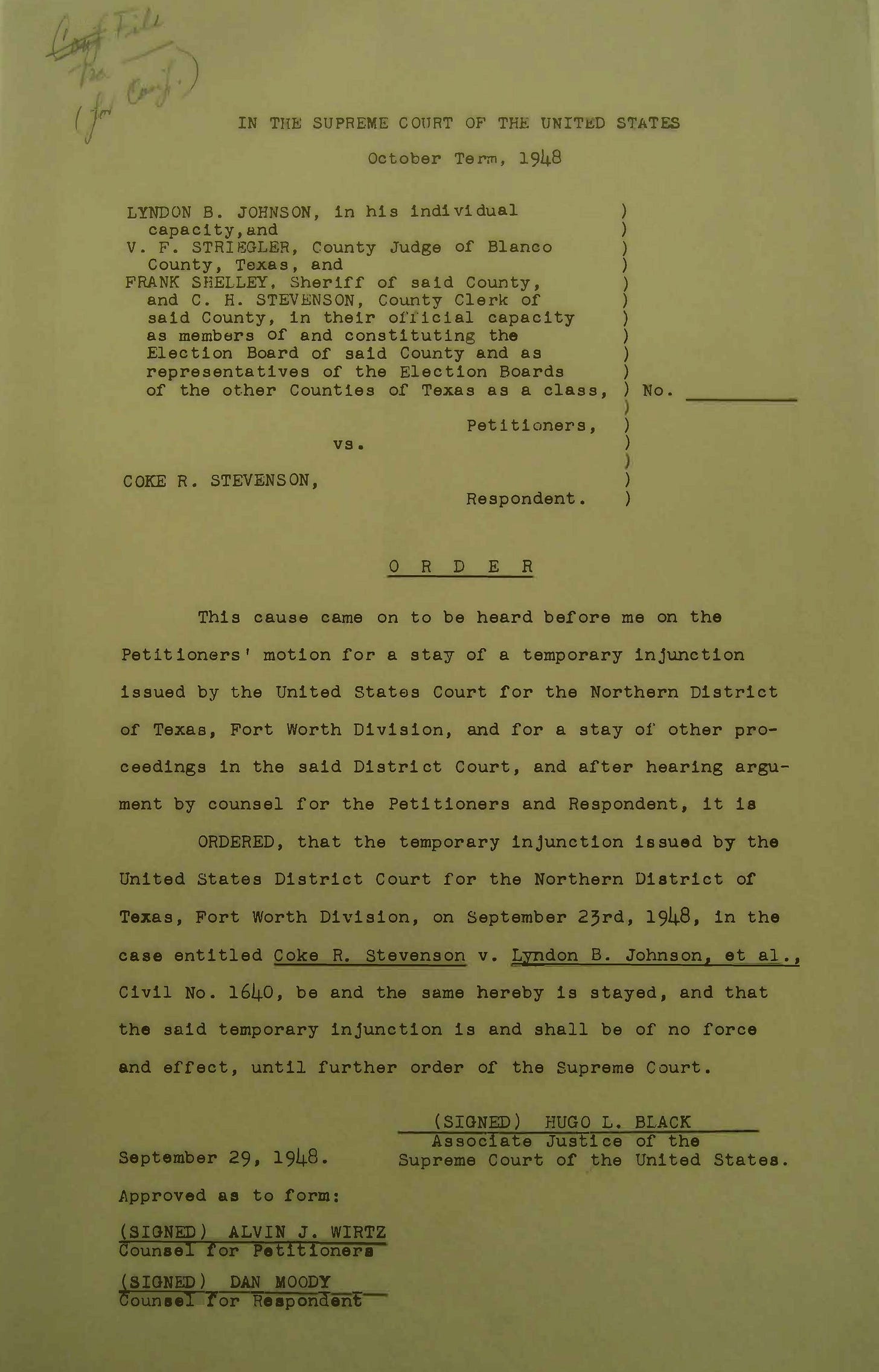

This week’s “Long Read” was inspired by an anniversary that came and went yesterday—one of the more historically significant pre-1980 grants of emergency relief by a Circuit Justice that I encountered in researching my book. On Wednesday, September 29, 1948, Justice Hugo Black, as Circuit Justice for the Fifth Circuit, issued a stay of a district court injunction arising out of claimed improprieties in the 1948 Texas Democratic Senate primary. The formal effect of the stay was to clear the way for the Texas Democratic Party to certify then-Representative Lyndon Baines Johnson as the victor—in a state in which the winner of the Democratic primary was all-but-assured of victory in the general election. The practical effect was to shut down the investigation into claims that LBJ’s supporters had stolen the election through brazen fraud in two adjacent counties in the Rio Grande Valley. And in the middle of all of it was Johnson’s personal lawyer and a future Supreme Court Justice in his own right—Abe Fortas.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

The full Court handed down four orders last week—denying emergency relief in three separate applications by Missouri death-row inmate Marcellus Williams (one of which provoked public dissents from Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson); and in an application by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., seeking to get back on to the New York presidential ballot.

Justice Alito, as Circuit Justice for the Fifth Circuit, also issued an “administrative” stay in a potentially significant non-delegation case—giving the Court more time to decide whether to freeze a Fifth Circuit ruling that had struck down the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act of 2020 (HISA) on the ground that it unconstitutionally delegated regulatory enforcement authority to a private entity (the Horseracing Safety and Integrity Authority), while the affected parties appeal. The Solicitor General, who is also a party in the case, filed an interesting “response” agreeing with the applicants that emergency relief is warranted—and flagging that the Justice Department is itself planning to file a cert. petition today challenging the Fifth Circuit’s analogous (if even more significant) ruling in the Consumers’ Research case.

Justice Alito called for the plaintiffs challenging the HISA to respond to the application by this afternoon—but did not impose any sunset on the administrative stay, which will therefore remain in effect until the full Court rules. All of this is to say, the real story here is that it sure looks like the Supreme Court is going to have significant private non-delegation issues on its docket later this term—regardless of what happens here.

Speaking of today, the justices meet later this morning for their annual “Long Conference.” There are more than 300 petitions for certiorari among the matters the justices are set to consider today—although we know they’ll only “discuss” a very small percentage of them. Still, the Long Conference tends to produce as many new grants as any other Conference throughout the term. We won’t get the regular orders out of the Long Conference until next Monday at 9:30 ET. But the Court should issue miscellaneous orders (perhaps some of the grants and rulings on other pressing matters) either later today or tomorrow.1

Other than those orders, we don’t expect anything this week. Of course, the justices are still sitting on 20 emergency applications—including the three different sets of environmental law cases, all of which are now ripe (if not overly ripe) for decision. So we could get some other significant rulings this week—or not.

The One First “Long Read”:

Abe Fortas, Hugo Black, and … LBJ

If it weren’t for the shadow docket, you might never have heard of Lyndon Baines Johnson.2 Nearing the end of his sixth term as a relatively anonymous congressman from the Texas Hill Country, Johnson bet his political career on winning the 1948 Democratic nomination for Texas’s open Senate seat—in a state in which whoever won the Democratic primary was all but assured of victory in the general election. On primary day, Johnson finished second, 70,000 votes behind former governor Coke Stevenson. But Stevenson did not have enough votes in a crowded field to avoid a runoff, so the race came down to a head-to-head matchup between the two.

Stevenson was an old-school conservative Texas Democrat—a segregationist and unapologetic racist widely known as “Mr. Texas.” Johnson was more closely aligned with the New Deal wing of the Democratic Party, with perhaps even more support in Washington than in his own state. Johnson was also desperate to win, throwing an unprecedented amount of money and influence into the runoff. That included enlisting friendly political bosses in parts of Texas where it was widely believed that elections followed the Joseph Stalin model—that it wasn’t the votes that counted, but rather who counted the votes. Johnson’s efforts had an impact: when the results came in on the night of the runoff, he appeared to have lost by fewer than 1,000 votes. Over the next few days, “adjustments” closed the margin to just over 100 votes as precincts “corrected” erroneous election-night reports. Still, it appeared that that’s where the election (and Johnson’s career) would end.

Then, six days after the runoff, 202 additional votes were miraculously reported from Precinct 13 of Jim Wells County in South Texas, in the tiny town of Alice.3 Remarkably, 200 of the 202 late-discovered ballots had been cast for Johnson. And, according to Stevenson and a witness who saw the voter roll before it mysteriously disappeared, the names of those last 202 voters on the tally sheet were in alphabetical order, which was a rather improbable coincidence, to say the least. Worse still, they appeared to be in the same pen and handwriting, which were themselves different from the other entries on the list. Stevenson also tracked down the last person listed as having voted before the late-discovered names, who swore that he had voted twenty minutes before the polls closed, and that no one else had been waiting to vote after him.

The votes from “Box 13” put Johnson ahead by 87 votes out of nearly 1 million cast—a lead of 0.008 percent. This wasn’t Johnson’s first election-fraud rodeo. In a 1941 special Senate election, he’d had the Democratic nomination stolen from him in a similar fashion—via late-reported votes from his opponents’ strongholds. To this day, it’s not clear whether Johnson knew in advance about the similar efforts of his allies in 1948. But what is clear is that Johnson worked tirelessly behind the scenes afterward, first to block any attempt at a recount in Jim Wells County, and then to get the executive committee of the state Democratic Party to certify the result, which it did the following Monday in a contentious, dramatic, and nail-biting 29–28 vote. Referring to himself as “Landslide Lyndon,” Johnson declared victory.

At that time, parties—not states—ran primary elections, and post–Election Day shenanigans in close races were more the norm than the exception, especially in Texas. But even by those low standards, the Box 13 episode was extreme. With witness testimony casting grave doubt on the integrity of the late-reported Box 13 totals, Stevenson persuaded Dallas federal judge T. Whitfield Davidson to issue an injunction blocking the state Democratic Party’s certification of Johnson’s victory until the electoral fraud claims could be fully investigated. Davidson appointed a special master to conduct a full- scale investigation into the matter (and a second special master to investigate irregularities in neighboring Duval County). Not only would such an inquiry potentially spell doom for Johnson, but it also increased the possibility that, either way, the ballots for the November general election would be printed with no Democratic candidate on them—unless the matter could be resolved by the state’s fast-approaching October 3 ballot-printing deadline.

The mounting drama in Texas had nationwide implications. Having lost control of Congress in the 1946 midterms for the first time in fourteen years, Democrats were desperate to retake control of the Senate, and holding onto the safe Texas seat was essential to that goal. More than that, the rift between Johnson and Stevenson mirrored the broader schism between the Democratic establishment and the “Dixiecrats”—southern Democrats opposed to the party’s turn toward civil rights, who supported Strom Thurmond, rather than the incumbent president, Harry S Truman, for the party’s nomination for president. Thus, across the country, all eyes turned to the legal proceedings in Texas.

On Monday, September 27, 1948, William Robert Smith Jr., formerly the U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Texas and now the special master appointed by Judge Davidson to investigate Box 13, convened a hearing in the local courthouse in Alice, and began to take testimony from witnesses and collect the sealed ballot boxes. By Tuesday afternoon, he was perhaps minutes away from either locating the missing tally sheet from Box 13 (which would presumably prove the fraud) or proving that all three copies of the list had been destroyed. Either outcome would only further inculpate Johnson’s local allies. But then, Supreme Court justice Hugo Black intervened.

Johnson’s legal team, headed by Abe Fortas (whom Johnson would appoint to the Supreme Court in 1965), had already asked Fifth Circuit judge J. C. Hutcheson Jr. to stay Judge Davidson’s injunction. But Hutcheson had ruled on Friday, September 24, that he had no power to act by himself, and that Johnson would have to wait until the full Fifth Circuit reconvened on October 4 (i.e., the day after the Texas ballot-printing deadline).4 The next morning (Saturday, September 25), Fortas called Black, asking him in his capacity as circuit justice for the Fifth Circuit to stay Judge Davidson’s injunction and allow Johnson’s name to be printed on the ballot.

On the morning of Tuesday, September 28, Black, who had been a New Deal–supporting Democratic senator from Alabama before his elevation to the Court in 1937, heard four hours of argument on the matter in his Washington chambers. That afternoon, he issued an oral ruling staying Judge Davidson’s injunction. As relayed in a firsthand account by Lewis Wood (a New York Times reporter), Black concluded that no statute authorized Judge Davidson to “suspend the process of electing a Senator or Governor.” When he formalized the order in writing the next day, he provided even less analysis, simply noting that he was issuing a stay pending further order of the Court, without any explanation as to why.

And although Black’s stay only froze the injunction, Judge Davidson understood it, perhaps overbroadly, to also freeze the ongoing investigations into Box 13 and other voting irregularities—which were stopped in their tracks, never to resume.

On Saturday, October 2, Stevenson asked the full Supreme Court to lift Black’s stay, arguing that Black lacked the authority to rule by himself. Fortas responded on behalf of Johnson, encouraging the full Court to either affirm Black’s order or to stay Judge Davidson’s injunction itself. But especially with the ballot-printing deadline on Sunday, the rest of the justices wanted nothing to do with the dispute. On the afternoon of Monday, October 4—the “First Monday” of the October 1948 Term—the justices voted 8–0 to deny both Stevenson’s and Johnson’s motions (the orders were handed down the following morning; Justice Frank Murphy did not participate due to illness). So the last word belonged to Black.

Life magazine called it “the eighty-seven votes that changed history.” If anything, that was an understatement. Four weeks later, Johnson won the general election with 66 percent of the vote. Two months thence, he was sworn into the Senate. Within two years, Johnson would be the majority whip. Two years after that, he’d be the majority leader. And the rest was, indeed, history—history that would have looked very different without the stay issued by Justice Black and the behind-the-scenes maneuvering of future Justice Fortas.

Johnson himself acknowledged as much: when he hosted an eightieth birthday party for Justice Black at the White House in 1966 (by which point Fortas was Black’s newest colleague on the bench), he concluded, in his toast, that “if it weren’t for Mr. Justice Black at one time, we might well be having this party. But one thing I know for sure, we wouldn’t be having it here.”

SCOTUS Trivia: In-Chambers Arguments

I’ve written before about the pre-1980 phenomenon of “in-chambers arguments”—when circuit justices would hold oral argument on emergency applications on their own. Many, like the argument before Black in Johnson, were actually in the circuit justice’s chambers. Some, like the famous August 1973 argument before Justice Douglas in Holtzman v. Schlesinger, … weren’t. (Holtzman was argued at the U.S. federal courthouse in Yakima, Washington.)

The practice abruptly died out in 1980—at the exact same time as the Court (1) stopped formally adjourning over its summer recess; and (2) appears to have begun referring even potentially divisive emergency applications to the full Court. (We still see a handful of in-chambers opinions, but Chief Justice Roberts’s March 2024 opinion in Navarro was the first example in almost a decade.)

The trivia is the very last time a justice heard an in-chambers argument. It appears to be Justice Marshall, as Circuit Justice for the Second Circuit, in Blum v. Caldwell—on May 5 (or perhaps May 6), 1980.5 Marshall issued a seven-page ruling on May 6 denying the application—but it’s unclear whether the argument was earlier that day or the day before (when the application had been filed).

Marshall’s opinion is pretty par for the course for that era—circuit justices carefully analyzing the equities and explaining why it didn’t (or, in other cases, did) make sense to intervene. Trivia aside, I continue to think that the pre-1980 approach may have been a better model than the one that replaced it.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday!

If you’re wondering why the Court doesn’t just wait until next Monday to announce grants, it’s a matter of timing. The Court’s usual briefing schedule takes roughly 17 weeks from a grant to oral argument. The January 2025 argument session starts on January 13, i.e., 15 weeks from today. So granting today (or tomorrow) versus next Monday allows for the possibility that the newly granted cases to be argued in January—with less compression of the briefing schedule.

This discussion is drawn from Chapter 6 of The Shadow Docket: How the Supreme Court Uses Stealth Rulings to Amass Power and Undermine the Republic (2023).

There is some dispute as to whether there were 201 late-discovered votes rather than 202. All agree that Johnson himself received exactly 200 new votes (allegedly because the local election judge changed the number on the precinct tally sheet from 765 to 965). Whether Stevenson received one or two more votes is—and always has been—a distinction without any real difference.

There is some suggestion that Fortas had deliberately engineered this exact result—applying to Hutcheson alone in the hope that it would allow him to get the matter before Justice Black faster.

The indispensable Supreme Court Practice treatise refers to the last in-chambers argument as occurring in 1980—but doesn’t cite to a specific one. It’s possible there was a later in-chambers argument during that same year; I’ll just say that, if so, I haven’t been able to find any evidence of it.

It was amazing to read the account of the 1948 election in Texas. Back in 1980 or 81 I worked in a small store in Louisiana. Our customers often liked to hang around and talk. One customer's conversation never left me. I have a BA in History, so the story was particularly interesting to me. I don't recall the man's name, but I remember the story very well. He was from the same area of Texas where Johnson was a politician. He told me that when he was 10 years old, some nice people, friends of his parents I believe, asked him if he wanted to make some money. What they did was pay him a few dollars for each polling place they took him to, and his "job" was to vote for Lyndon Johnson. Needless to say, I was amazed by this. I remember that he was someone who would have been about 10 in 1948. Until now, I have never heard anything about this shady election and I was astounded to read the account. Thank you for filling in the blanks for me!!

Buried by plutocrocy to end Expression antithetical POSITIONS in my imperfect UNEDUCATED ILLITERATE BRAIN'S assaulted breaths contributions continually BETTING GAMES SADISTIC 🎮 victoriously in defense against him in grace's sentient BREATHS RESOLVED MY EYES REFLECTIONS I AM CONTINUALLY UNDERSTANDING TOMORROW'S self interest by our REPUBLIC STALWARTS you will be free from our foes of God in the presence GATHERED THROUGH confusions antithetical democratic principles antigovernment mind-drilling in my faith in this vessels attrition FINALLY GOT seen.