100. Same-Sex Marriage and the 2014 Long Conference

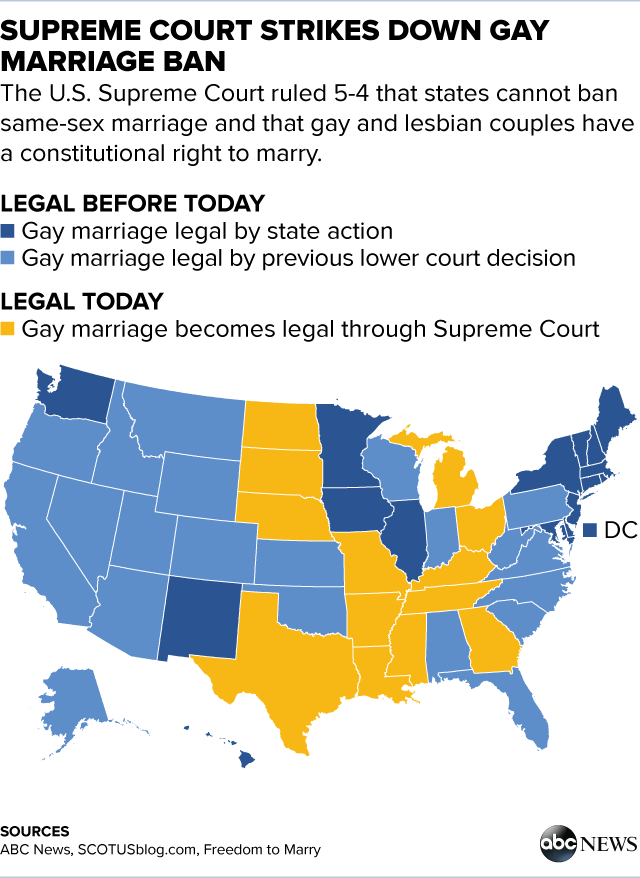

Same-sex marriage became legal in more states through cert. denials (18) than through the Court's June 2015 ruling in Obergefell (13). Strategic voting by Chief Justice Roberts is a big part of why.

Welcome back to “One First,” a weekly newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us.

Every Monday, I’ll be offering an update on goings-on at the Court (“On the Docket”); a longer introduction to some feature of the Court’s history, current work, or key players (“The One First ‘Long Read’”); and some Court-related trivia. If you’re enjoying the newsletter, I hope you’ll consider sharing it (and subscribing if you don’t already):

This week’s “Long Read” was inspired by the upcoming tenth anniversary of the Court’s October 6, 2014 Order List—an event that might not seem especially anniversary-worthy. As it turns out, though, that Order List, coming out of the justices’ 2014 Long Conference, included some of the most significant denials of certiorari in the Court’s history. Specifically, the justices denied seven petitions that, between them, sought review of three circuit-court rulings—each of which had affirmed district court rulings that struck down state same-sex marriage bans. The Court’s denials of certiorari had the effect of putting those district court rulings into effect—and clearing the way for same-sex marriage in the states at issue.

Indeed, it’s a straight line from those cert. denials to the legalization of same-sex marriage in 18 states. When you include `the 19 states that had already legalized same-sex marriage on their own, that means that same-sex marriage became legal in more states because of cert. denials than because of the Court’s June 2015 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges. And as I explain below, some strategic voting by Chief Justice John Roberts—one of the four dissenters in Obergefell—was a big part of how that happened.

But first, the news.

On the Docket

It was another outwardly quiet week from the Court. The only two orders from the Court came on Friday—a denial, over no public dissents, of the Nevada Green Party’s emergency request to put Jill Stein on presidential ballots in the Silver State; and a denial, over a public dissent from Justice Sotomayor, of a request for a stay of execution (and for plenary review) from South Carolina inmate Freddie Owens.

We’re still waiting for movement on any of the three sets of emergency applications relating to new EPA rules—all of which are now ripe for some decision from the Court. I’ll just keep repeating that the challenges to the new limits on power-plant emissions are the longest outstanding applications … until they’re not anymore.

Otherwise, we don’t expect anything scheduled out of the Court this week; next Monday is the justices’ 2024 “Long Conference,” where the Court will meet in person to clear out the backlog of appeals and miscellaneous matters that piled up over the summer. More on that next week.

The One First “Long Read”:

The Significance of the Same-Sex Cert. Denials

Even though the Supreme Court dodged the constitutionality of California’s same-sex marriage ban in its June 2013 ruling in Hollingsworth v. Perry, its decision that same day in United States v. Windsor, striking down part of the Defense of Marriage Act, sparked a new round of challenges to same-sex marriage bans.1 By the summer of 2014, three circuits—the Fourth, Seventh, and Tenth—had affirmed district-court rulings that had enjoined state same-sex marriage bans based upon Justice Kennedy’s reasoning in Windsor. The Tenth Circuit ruling came on an appeal by Utah; the Fourth Circuit ruling came on an appeal by Virginia; and the Seventh Circuit ruling came on an appeal by Wisconsin. Because the Seventh and Tenth Circuits had subsequently rejected two other states’ appeals, the Supreme Court was soon confronted with a total of seven petitions for certiorari from five different states, all asking the justices to resolve the marriage question one way or the other. And because states and lower courts had learned their lesson from the earlier (chaotic) aftermath of the Utah case,2 no same-sex marriages were being performed in these states pending the outcome in the nation’s capital.

The seven petitions were each considered by the Supreme Court on Monday, September 29, 2014, during its “Long Conference,” the name given to the justices’ first formal meeting after their summer recess, at which they consider all the petitions for certiorari and other nonemergency procedural matters that have accumulated over the summer. One week later, at 9:30 a.m. on the “First Monday” of the October 2014 Term, the Court denied 1,575 petitions for certiorari. Most of the denials were not surprises. But among those rejections were all seven of the marriage cases, denials that, as Professor William Eskridge and Christopher Riano note in their book Marriage Equality: From Outlaws to In-Laws, “flabbergasted” the legal community. If that weren’t surprising enough, no justice publicly noted a dissent from any of the seven orders.

The Supreme Court’s denials of certiorari in the marriage cases were dramatic in more ways than one. In the five states whose bans were at issue, the Court’s summary orders had immediate effects. Not only did the denials of certiorari leave in place federal court rulings that had struck down marriage bans in each of those states, but the stays that were in place in those cases immediately dissipated. By the afternoon of October 6, clerks were issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples in Oklahoma, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin. In Indiana, licenses became available the following morning.

But the impact went far beyond those five states. By denying certiorari, the Court had not just rejected five states’ defenses of their own marriage bans; it had refused to disturb the rulings of three different federal appeals courts, which supervised the federal courts not just in those five states, but in six other states with marriage bans on the books. In each of those states, the court of appeals’ rulings invalidating another state’s marriage ban was now precedent that bound each of the federal district courts. As district courts put those appellate rulings into effect in pending suits challenging other states’ marriage bans, the Supreme Court’s October 6 cert. denials thus led to marriage equality in Colorado (on October 7, 2014); West Virginia (October 9); North Carolina (October 10); Wyoming (October 21); Kansas (November 12); and South Carolina (November 20).

In one fell swoop, the Supreme Court’s summary, unsigned, and unexplained decisions to stay out of the marriage issue on October 6 had directly legalized same-sex marriage in eleven states. And the justices soon legalized same-sex marriage in six more states. In what was surely not a coincidence of timing, the day after the Supreme Court’s denials of certiorari on October 6, the Ninth Circuit reached the same conclusion as the Fourth, Seventh, and Tenth Circuits in an appeal brought by Idaho, holding that all state marriage bans—and not just California’s, which it had already struck down—violated the federal Constitution. Nevada declined to pursue its own appeal further, so same-sex marriage became legal there on October 9, 2014. And when Idaho asked the Supreme Court to stay the Ninth Circuit’s decision the following day, the Supreme Court refused, once more through a summary order with no noted dissents.

Alaska and Arizona followed on October 17, and Montana on November 19. Even the deeply conservative Eleventh Circuit (covering Alabama, Georgia, and Florida), which would never rule on the merits of any state marriage bans, refused to pause a Florida district court ruling blocking that state’s marriage ban while Florida appealed. When the Supreme Court likewise turned away Florida’s attempt to freeze the district court order, it effectively legalized same-sex marriage in the nation’s fourth-largest state on January 6, 2015. In total, between the October 6 cert. denials and the subsequent stay denials, the Supreme Court had legalized same-sex marriage in seventeen states in exactly three months through unsigned, unexplained orders. What’s more, only Justices Scalia and Thomas registered public dissents from any of the stay orders, suggesting that the rest of the Court was perfectly happy to continue this pattern, perhaps until same-sex marriage was legal nationwide.

But one federal appeals court had other ideas. In a lengthy ruling issued on November 6, 2014, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit upheld marriage bans in each of its four states—Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee. Writing for a 2-1 majority, Judge Sutton wrote that, despite the writing on the wall, the court could not simply assume that the Supreme Court’s consistent procedural actions on and after October 6 were meant to have substantive effects:

Don’t these denials of certiorari signal that, from the Court’s perspective, the right to same-sex marriage is inevitable? Maybe; maybe not. Even if we grant the premise and assume that same-sex marriage will be recognized one day in all fifty States, that does not tell us how—whether through the courts or through democracy. And, if through the courts, that does not tell us why— whether through one theory of constitutional invalidity or another. . . . If a federal court denies the people suffrage over an issue long thought to be within their power, they deserve an explanation. We, for our part, cannot find one, as several other judges have concluded as well.

In essence, the Sixth Circuit’s decision in DeBoer v. Snyder was both a loud public dissent from the Supreme Court’s efforts to quietly legalize same-sex marriage through denials of certiorari and, at the same time, a fatal obstacle to the success of those efforts; the ruling created a circuit split, thus forcing the Supreme Court’s hand.

Each of the plaintiffs in DeBoer quickly sought review from the Supreme Court. Their petitions presented as compelling a case for certiorari as the justices ever receive: There was now a disagreement among five federal courts of appeals as to an incredibly significant constitutional question affecting millions of Americans. Only the Supreme Court could conclusively break that logjam, and only by issuing a ruling on the merits. So it was that, on January 16, 2015, the justices granted the four petitions challenging the Sixth Circuit’s ruling and consolidated them into a single case—Obergefell v. Hodges.

And yet, even after agreeing to resolve the marriage question on the merits once and for all, the Supreme Court used an unsigned, unexplained order to legalize gay marriage in one final state. This time, it was Alabama. On January 23, 2015 (one week after the Court agreed to take up the four Sixth Circuit appeals), Alabama district court judge Callie V. S. Granade struck down her state’s ban on same-sex marriage. Judge Granade stayed her ruling for fourteen days to allow either the Eleventh Circuit or the Supreme Court to extend the stay if they so desired. But the Eleventh Circuit refused on February 3, and the Supreme Court followed suit on February 9, at which point Alabama became the eighteenth state in which the Supreme Court had effectively legalized same-sex marriage, and the thirty-seventh with marriage equality, as of February 2015.

This time, Justice Thomas, joined by Justice Scalia, did not just publicly note his dissent from the majority’s summary, unsigned, and unexplained one-sentence order; he published a dissenting opinion memorializing his objections. In his separate statement, Thomas expressed surprise that the majority was allowing the district court’s ruling to go into effect when it had just agreed to take up the same question on the merits in the Sixth Circuit cases. As he wrote, when the Court had refused to freeze lower-court rulings after the October 6 cert. denials, “there was at least an argument that the October decision justified an inference that the Court would be less likely to grant a writ of certiorari to consider subsequent petitions.” A stay could be denied in those cases simply on the ground that it was unlikely that the Court would take up the appeal on the merits, which was one of the four traditional criteria for such relief. There isn’t much point in pausing a ruling pending an appeal that won’t be heard. But, as Thomas explained, thanks to Obergefell, “that argument [was] no longer credible”: “The Court has now granted a writ of certiorari to review these important issues and will do so by the end of the Term.”

On this point, Justice Thomas was clearly correct. What then, explained the Court’s refusal to stay Judge Granade’s ruling in the Alabama case while it was preparing to resolve the exact same constitutional question in Obergefell that she had just resolved against Alabama? The answer, in retrospect, is obvious: even though the oral argument in Obergefell was still well over two months away, the justices knew how they were going to rule. Before the Sixth Circuit decision, it was at least plausible that the Court had just been keeping its head down, and that its nonintervention was simply a delaying tactic, rather than an intimation of how it would eventually rule on the merits, assuming it ever had to. One could perhaps even argue that it still wasn’t clear how the Court would rule as late as January 16—when it agreed to review the Sixth Circuit cases on the merits. Perhaps there was a majority to side with the Sixth Circuit in upholding state marriage bans, rather than siding with the four other circuits that had struck them down. After all, if the justices ended up deciding to uphold state marriage bans, the price would only have been akin to what happened in Utah—allowing a few thousand same-sex marriages to be performed in the interim, which at least some of the justices might have deemed worth it in exchange for trying to stay out of the matter altogether.

But the fact that the Court allowed same-sex marriages to go forward in Alabama even after formally agreeing to decide the issue in Obergefell was as clear a signal as the justices could possibly have sent about which way the wind was blowing. If they were planning to uphold bans like Alabama’s, it would make little sense to allow same-sex marriages to proceed there for no more than five months before halting them. If same-sex marriage was soon to become the law of the land, on the other hand, why make couples wait any longer? By doing nothing, it turns out that the Supreme Court had already done quite a lot.

There’s one more footnote to the Supreme Court’s efforts to legalize same-sex marriage in eighteen states prior to Obergefell, but it’s an important one. As with any Supreme Court case decided through a signed majority opinion, we know the vote count in Obergefell: it was the same 5–4 split as in Windsor, with Justice Kennedy joining the four justices appointed by Democratic presidents—Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan—in the majority; and Chief Justice Roberts, joined by Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito, in dissent.

That there were four dissenters when the Supreme Court finally resolved the marriage issue in Obergefell is a revealing part of this narrative, because it takes only four votes to grant certiorari. Thus, if the same four justices who dissented in Obergefell—and voted to uphold state bans on same-sex marriage—had wanted the Court to review the earlier circuit court rulings that had struck down such bans, they could have forced the issue, by voting to grant any (or all) of the seven petitions that had been denied on October 6, 2014. In other words, at least one of the justices who dissented from the Supreme Court’s decision to recognize a federal constitutional right to same-sex marriage in Obergefell had nevertheless voted to deny certiorari in each of the seven petitions the Court denied on October 6. At least one of the Obergefell dissenters was thus willing to allow the Court to legalize same-sex marriage through unsigned and unexplained orders; he just refused to sign on when the time came to issue an opinion on the merits. We can be fairly sure, because of their dissents from several of the stay denials, that it wasn’t either Justice Thomas or Justice Scalia. That leaves Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito. And for what I suspect are fairly obvious reasons, it was almost certainly Roberts.

In other words, it certainly at least seems as if Chief Justice Roberts was willing to let the Supreme Court legalize same-sex marriage so long as it did so through unsigned, unexplained cert. denials. Once the Court had to resolve the issue on the merits, the Chief ended up in dissent. As a lesson in how the justices behave strategically throughout the certiorari process, the same-sex marriage cases are striking. And as an example of a high-profile issue where the Chief Justice was willing to leave intact lower-court rulings with which he disagreed if it meant the Court could stay out of the matter, the same-sex marriage cases are, perhaps, a relic of history.

SCOTUS Trivia: Why was the Supreme Court Case Called Obergefell?

As noted above, the Sixth Circuit decision that the Supreme Court reviewed in Obergefell came under the caption DeBoer v. Snyder—the parties to the lawsuit challenging Michigan’s same-sex marriage ban. But in the Supreme Court, the caption was that of the Ohio case—Obergefell v. Hodges.

The reason for this difference is entirely trivial—but hey, that’s the point! When the plaintiffs who lost in the Sixth Circuit filed their cert. petitions in the Supreme Court, it was Obergefell’s that was filed and docketed first—as No. 14-556. (The other three were docketed as Nos. 14-562, 14-571, and 14-574.) So when the Court granted certiorari in all four cases and consolidated them, it (as a matter of course) consolidated them under the caption of the lowest docket number—Obergefell. Indeed, whenever the Court consolidates multiple cases into a single ruling, it’s always the lowest docket number that provides the caption.

Sometimes, it helps to be first…

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this installment of “One First.” If you have feedback about today’s issue, or thoughts about future topics, please feel free to e-mail me. And if you liked it, please help spread the word!:

If you’re not already a paid subscriber and are interested in receiving regular bonus content (or, at the very least, in supporting the work that goes into this newsletter), please consider becoming one! This week’s bonus issue for paid subscribers will drop on Thursday. And we’ll be back with our regular content for everyone next Monday!

Today’s “Long Read” is adapted from Chapter 2 of The Shadow Docket: How the Supreme Court Uses Stealth Rulings to Amass Power and Undermine the Republic (2023).

In December 2013, a district court had enjoined Utah’s same-sex marriage ban—and then not stayed that ruling pending appeal, which allowed for a small but significant number of same-sex marriages to be performed in the state. The Supreme Court issued a stay soon thereafter—keeping Utah’s marriage ban on hold until after the Court denied certiorari in the Tenth Circuit case.

Chris Geidner also wrote an article about this topic. Alito's vote is interesting.

https://www.lawdork.com/p/scotus-shadow-docket-steve-vladeck

Steve,

I was bewildered: how can 14-566 be lower than 14-562. Your fact-checking team failed you. Obergefell's docket number is 14-556. Just helping to keep the numbers straight.

Thanks for all your thoughts on this. Mike L.